Journey Post 49: While You Were Away…

The Parable of the Wicked Tenants, Matthew 21:28-46

Jesus was challenged a number of times by the religious establishment about his authority for doing and saying the things he did. Ordinary people simply recognized his authority. Jesus was no threat to the “little people”; they were not at risk of losing their power, as the leaders were. The “Sermon on the Mount,” for example, left people amazed because Jesus did not cite esteemed rabbis as other teachers did. He said, “You have heard it said…but I tell you….”

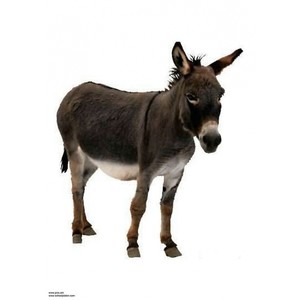

To set us up for the parable, picture the scene: Jesus has just entered Jerusalem on a donkey amid the shouts and praises of the people. The city is abuzz with excitement because many wondered if he might be their long-awaited Messiah. He drives the money-changers and dove sellers out of the Temple, then heals many blind and lame. The angry leaders complain to Jesus about children shouting and praising “the Son of David” (a messianic title).

Then the priests and elders demand to know, “By whose authority do you do these things?” Jesus answers: “If you will tell me by whose authority John baptized, I will tell you.” At this, the leaders balk, whispering among themselves: “If we say, ‘from heaven,’ he will ask why we didn’t believe him. But if we say it was merely human, we’ll be mobbed because the people believe John was a prophet.” So they say, “We don’t know.”

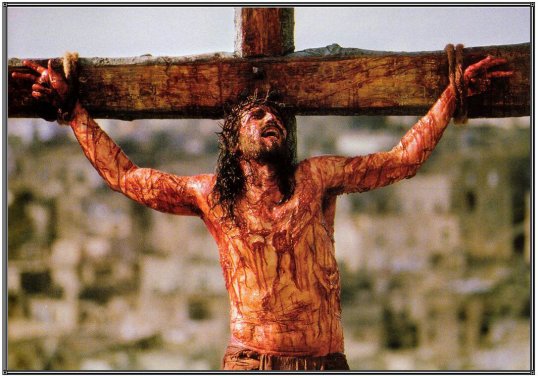

Things are now coming to a head between Jesus and the religious leaders in Jerusalem: five days later, they will succeed in getting rid of their nemesis—or, so they think.

In Matthew 21, Jesus tells two parables.[1] The point of the first one is not obvious to the leaders—until Jesus ties it to their rejection of John the Baptist. The second one hits home right away.

Why is Jesus increasingly angry and condemnatory of these leaders? After all, in America when some preacher or church is phony or false or just plain weird, we can go to a thousand others. Not so in Israel. It’s important to get this point, and to know God’s expectations. Otherwise, we may read the story only as confirmation of how hypocritical, self-centered, and self-protective the religious leaders were. Yes, they were false teachers: Could not people just ignore them and walk away?

No. There were no others. The religious leaders held positions invested with the authority of Moses himself. They had been given a charge by God to be stewards of his people, to be “good shepherds” who would feed them spiritually and protect them from spiritual charlatans and wolves. Instead, as Jesus told them, they loaded impossibly heavy burdens onto the people.

Think about the teachers you’ve had in school, church, military, in all of life—including parents, anyone who has held a certain amount of authority over you. Some were good, some bad, most were a mix. We consciously imitate the good ones—but they’ve all left their mark deep within our psyche.

Jesus came for many reasons: to die for our sins, to live a life in front of us that was pleasing to God, to teach us about his Father, and other things. The apostle John, who was a teen when he became a disciple and an old man when he penned the Gospel that bears his name, left us some vivid imagery about who Jesus is and what he came to do. One of the most vivid is that Jesus came as “the light of the world.” Light is reflected and so we see. In Jesus’s case, he reflected God.

His life was a picture of God far different from the one presented by those who occupied a position of stewardship in behalf of God.

The picture of God they reflected was a distortion, an insidious caricature of a God more interested in people’s external compliance with what they could do or not do, for example, on a Sabbath day, or how they could keep the letter of the law while ignoring its spirit. Their God was a judge never satisfied, a punisher of imperfect rule keeping.

The God Jesus reflects is a loving wise Father who wants to be known intimately and who intends that his people share his same perspective and values in dependence upon him, a Father who loves self-sacrificially and delights in his children like an ideal earthly father. His law is intended to instill his values, two above all else: loving God with all your heart, soul, mind, and strength, and your neighbor as yourself. Everything else comes from these two. Obedience to this God is a given, but the motive to obey gets tangled up with avoiding hell rather than wanting to please a father who delights in you unimaginably:

“We love him because he first loved us” (1 John 4:19).

Jesus explained to the teachers and Pharisees in no uncertain terms what their hypocrisy was really about: “You have neglected the more important matters of the law—justice, mercy, and faithfulness” (Matthew 23:23). They were saddling the people with heavy burdens while themselves living hypocritical lifestyles, seeking to maintain their own power and honor. They were self-righteous, supposing they were keeping the law and deserved cred for that from God himself. In reality, they despised those they thought beneath them. They did not value people as God does. Any value they acknowledged stemmed from compliance to rules, not the intrinsic value God gave the creatures he made in his own image. Jesus quoted the prophet Isaiah to them: “These people honor me with their lips, but their heart is far from me.”

Knowing this, you can see there is little mystery about the parable of the wicked tenants. Even the leaders got the point real fast. They somehow knew that Jesus was right about them. And they would see him die for it.

Read the parable of the two sons and then the one about the tenants, Matthew 21:28-46.

Just a few notes are in order here.

If you were asked what made the teachers, the Pharisees, etc., so bad, you might think first of their hypocritical legalism and their rejection of Jesus as Messiah. Jesus certainly excoriated them for those faults. But the worst fault might be captured in the term “false teachers.” They did not truly know the God whom they claimed to represent: If you’ve ever encountered a person who claimed to know someone personally and obviously didn’t—you can imagine the problem. These men were charged with interpreting and teaching the Scriptures, all the more important because most people did not have direct access to the Bible and were dependent on these teachers to be the voice of God.

Jesus had this to say about them to the people: “The teachers of the law and the Pharisees sit in Moses’ seat. So you must be careful to do everything they tell you. But do not do what they do, for they do not practice what they preach. They tie up heavy, cumbersome loads and put them on other people’s shoulders, but they themselves are not willing to lift a finger to move them…” (Matthew 23:2-4).

By contrast, Jesus had this to say about himself: “Come to me, all you who are weary and burdened, and I will give you rest. Take my yoke upon you and learn from me, for I am gentle and humble in heart, and you will find rest for your souls. For my yoke is easy and my burden is light” (Matthew 11:28-30).

By contrast, Jesus had this to say about himself: “Come to me, all you who are weary and burdened, and I will give you rest. Take my yoke upon you and learn from me, for I am gentle and humble in heart, and you will find rest for your souls. For my yoke is easy and my burden is light” (Matthew 11:28-30).

Jesus claimed to know the Father in a way that no one else could. That might lead you to think he was some sort of cult leader. (I hope, in some future series of essays, to write about the implications of what he taught about the Father, about who God is and what right Jesus had to claim such knowledge.)

A couple comments about the meaning of the figures Jesus uses are in order. Why was the story set in a vineyard with the owner being away and sending his messengers, including his son, to collect?

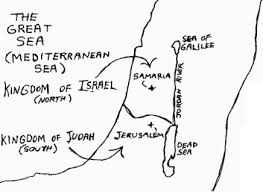

The owner, of course, is God. The tenants are the religious leaders, teachers and priests, allowed by the owner to work his vineyard. “Vineyard” is an important figure in Scripture, representing God’s people (Israel, during that time). When he sent representatives (prophets) to collect the “rent” (the portion of fruit the owner was entitled to receive), they beat some and killed some. The tenants, of course, were refusing to be held accountable, rejecting the owner and keeping the fruit for themselves, for their own gain. The “fruit” God was intending to see produced was the fruit of the two great commands. Like the fig tree, the false teachers proudly displayed their “leaves,” but bore no real fruit.

The tenants’ actions showed they didn’t grasp that their stewardship of the vineyard was only at the pleasure of the owner: it was his, after all. They did not value the owner, nor his servants, nor his son. Nor did they value the vineyard—i.e., those they were supposed to shepherd and steward–except as it was a benefit to them.

When Jesus asked what the owner should do, they knew: kill the wicked tenants and rent the vineyard to others who would produce the proper fruit.

If you’re involved in a church, you hear about false teachers from time to time. Unfortunately, such warnings are oftentimes couched in terms of doctrinal (teaching) differences that have little to do with the major teachings of the historic Christian faith. I saw this firsthand at a Bible school in Quebec years ago: one faction believed that Jesus carried his literal blood to the altar of God. So they split. Denominations do occasionally split over significant issues, but the details are often esoteric.

I would submit that Christian churches need to let the main thing be the main thing. The “main thing” is what I referred to above: the two great commandments, i.e., to love God with all that we are and to love others as ourselves. “There is no greater commandment than these,” said Jesus. It all starts from these. Love—genuine, self-giving and, yes, sacrificial—is a one-word summary of all God’s law.

I would submit that Christian churches need to let the main thing be the main thing. The “main thing” is what I referred to above: the two great commandments, i.e., to love God with all that we are and to love others as ourselves. “There is no greater commandment than these,” said Jesus. It all starts from these. Love—genuine, self-giving and, yes, sacrificial—is a one-word summary of all God’s law.

If these two are in place, the rest will sort itself out…whether God is present or away.

[1] Jesus cursed a fig tree, full of leaves but bearing no fruit (21:18-22). This was likely a demonstration for the sake of the disciples, a parabolic reference to the hypocritical leaders, though Jesus seemed to turn it into a lesson on faith.